Lessons from a Ghost Ride

Three forces that drive how we pursue health and self-improvement

Over the past two years, I've gotten into cycling - both for recreation and cardiovascular exercise. When I started, I wasn't recording any data: no distance, heart rate, or power metrics. Just me, the bike, and the road. Over time, like so many of us, I finally caved and created a Strava account.

“Did he just bring up Strava in the first three sentences of his blog post? Is this about to be an annoying, unrelatable, and self-congratulating fitness post?”

It’s not - Stay with me!

Last Saturday, I went through my familiar routine. I topped off the air in my tires, put my helmet on, clipped in, started Strava and headed to Prospect Park. I absolutely love this park. It’s charismatic and energizing. For me, it is the best park in New York City (sorry Central Park, Flushing Meadows Corona Park, and the many other honorable mentions), especially on a summer weekend. It's filled with families, music, and energy, lined with beautiful trees that create pockets of secluded forest within the urban jungle.

And I had one of my most enjoyable rides in months! I was in complete flow, convinced I might have even set a few personal records. It was a gorgeous day, and something about the entire experience just clicked.

I buzzed down the street from the park and hopped off my bike at home. Eager to capture the moment, I opened the Strava app to end the ride. I wanted to immediately savor the satisfaction of my journey, but instead of finding that digital memento waiting for me, I felt a sinking sensation: Strava had glitched and didn’t record the ride.

For a moment, I was shockingly annoyed. I lost touch with every element of the magic I just described. It took a beat, but the feeling slowly returned. Several minutes later, I was back to savoring the ride and the pride that came with it.

What a fascinating moment. Although fleeting, I experienced a real sense of loss. I'm not suggesting that missing Strava data is materially important - it's not. But I think we can learn quite a bit about ourselves when we pay attention to these seemingly mundane moments. As I reflected on this same feeling that my patients have described to me - regretfully forgetting to wear their Whoop, Oura, or Apple Watch during a workout - it raised the question:

"If you exercise and no device is around to record it, did it really happen?"

Of course it happened. But something real is stirring beneath the surface for all of us in these moments. Which made me wonder…

What triggers these feelings?

How do these moments reflect our relationships to ourselves and our health?

How do we balance the genuine utility of health data against an unhealthy dependence on it?

What's the right balance between accountability and a maladaptive need for external validation?

And as a physician, what can I learn from this to better help my patients?

Force #1 - The Utility and Dependence of Data

Data can often provide the structure to both understand our health and help us reach our goals, especially complex, long-term goals. Labs offer one of the clearest examples of this necessity. These are metrics we simply cannot intuit about our bodies - whether we have high cholesterol, elevated blood sugar indicating diabetes risk, or inflammatory markers suggesting underlying health issues. These numbers are essential for understanding our risks and how to address them. Even when lab results don't warrant medication, they can serve as powerful catalysts for behavior change, transforming abstract health concepts into concrete, actionable information.

Beyond clinical labs, fitness data operates on a similar principle, although the territory becomes more complicated. On a basic level, someone who wants to become a better runner might track the distance they run, gradually increasing it over time. This allows them to break long-term goals into manageable, short-term wins. Similarly, in the gym, one might track workouts and slowly add more reps and weight. These structures are objectively useful and often necessary to progressively build strength and exercise capacity over time.

Data can be a tool in our story - an incredibly useful tool. But problems arise when data itself becomes the story. At that point, we've lost sight of the activity's true purpose: getting healthier, feeling better, living more fully, etc.

Wearable devices have accelerated this dynamic in both directions. On one hand, they've accomplished something remarkable: shortening the feedback loop on amorphous, complicated goals (like "improve my health") by breaking them into small, actionable activities. On the other hand, we're now inundated with metrics, creating the risk of data dependence and making it increasingly difficult to distinguish meaningful signals from background noise.

My close friend Dr. Jack Penner (one of the best docs I know) wrote about this phenomenon in his piece Embodied Awareness & Health. He discusses how data can become an obstacle to interoception: our ability to sense and understand our body's internal signals (i.e. being “in-tune” with our bodies).

To build further on his work, we can apply these concepts on the level of the individual patient. For some with low interoception at baseline, data can be the lily pad that helps build initial body awareness. For example, with a patient who is not in tune with their sleep habits, we might look at basic sleep metrics together - duration, latency, and quality metrics - to kickstart a meaningful conversation around rest and recovery. Often, observing how alcohol affects various metrics (glucose, resting heart rate, or heart rate variability) can be quite powerful. Of course, it doesn’t inherently change the experience of the behavior (you’re still hungover!), but it might cue you in to parts of the experience that you were unaware of or suppressing, especially at lower “doses.”

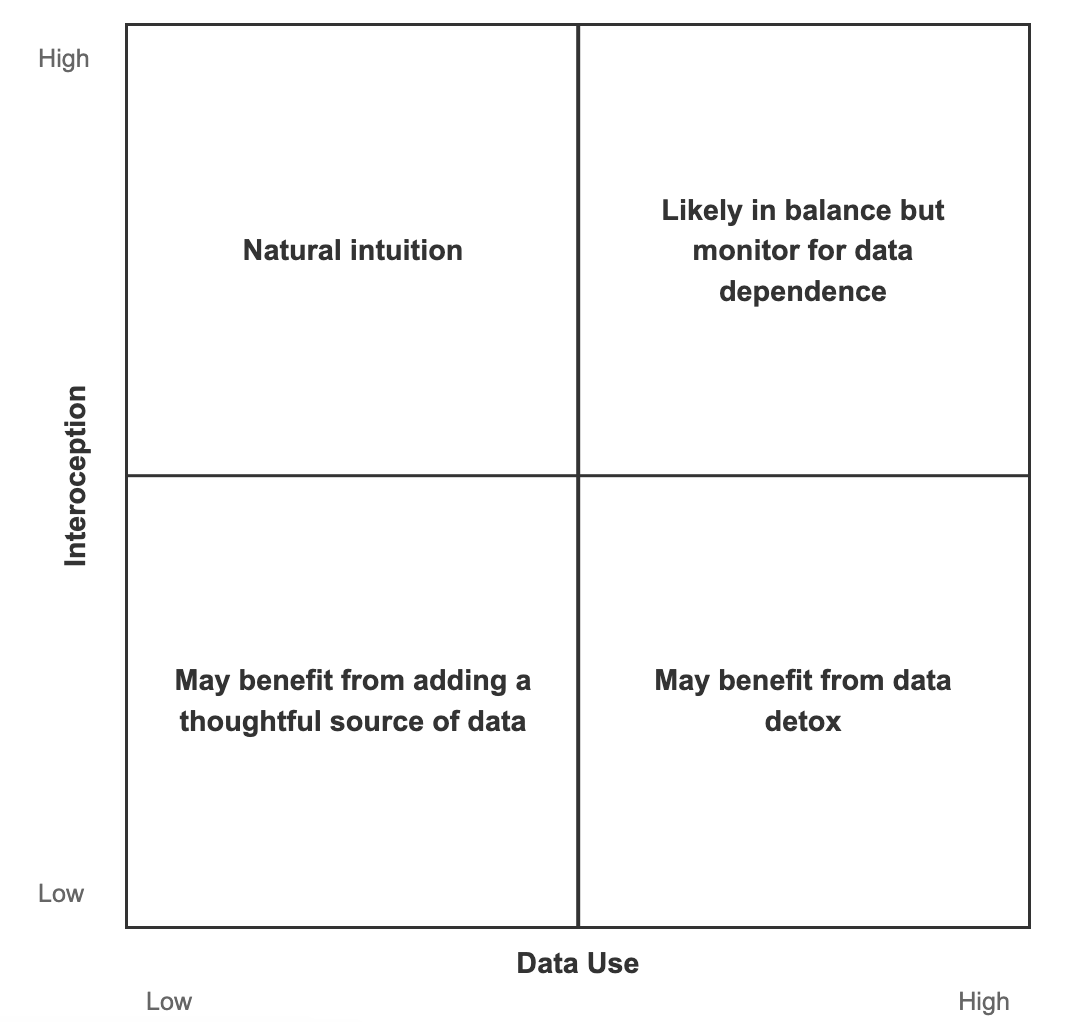

I love thinking in frameworks, and I use the following 2x2 in my practice to determine what might benefit each patient. Notably, the patients in my practice who have High Data Use x Low Interoception may be demonstrating “Data Dependence” and can often benefit from a “Data Detox”.

Many doctors dismissively tell you, "I don't need a wearable to tell you that alcohol is bad for you." This is true but a myopic perspective that ignores the complexity of behavior change. I need look no further than the countless patients who have been told by their doctors to "drink less," "eat better," or "exercise more" with no resulting change in their lives. I'll also sidestep the well-documented reality that physicians themselves have a complicated relationship with alcohol.

Force #2 - “Aren’t You Proud of Me?”

We learn how to be proud of ourselves by internalizing - at a very young age - how those close to us express pride in us. Imagine the young child with a scribbly piece of art in their hands, excitedly running to show it to their mother, who exclaims, "Wow, that's beautiful!" The child feels worthy and validated. Over time, they develop the ability to hold this validation internally, without needing the external feedback loop from others. When we share our wins with the world, there's a child within all of us asking, "Aren't you proud of me?" Don't mistake my invoking a child as suggesting this is immature. It's not. It's a fundamental human need.

This dynamic plays out everywhere in adult life: the professional who posts about their promotion on LinkedIn, the home cook sharing photos of their dinner, the parent documenting their child's first steps. We're all seeking that same validation loop on some level.

But there's a balance to strike. Healthy pride involves using external feedback as one source of validation while maintaining an internal sense of worth. It's the difference between sharing a workout because you're genuinely excited about your progress versus feeling empty when your post doesn't get enough likes. The former enhances our joy; the latter makes our self-worth contingent on others' responses.

When I lost my Strava ride, I lost a small but meaningful external feedback loop that I had been anticipating. I wanted to celebrate my accomplishment, and I honestly use those moments as tools to help cultivate pride in myself and my efforts. You might argue (and I would accept!) that in my described moment of loss, I was a bit too externally anchored. While I can only speak for myself, I have found that this trait runs pretty strong across modern society, especially in the “high-performing” professions and definitely across the “healing” professions: many of us have been wired to look externally before we can feel proud internally.

The key is, again, recognizing when these tools serve us versus when we serve them.

Force #3 - Community

Now, let's take the child described above and watch them become an adult navigating this interconnected world. While the child's need for validation from caregivers is foundational, adults develop a more sophisticated version of this same drive: the need for community belonging and shared purpose.

Humans are fundamentally social beings. We thrive when we feel seen, understood, and connected to others who share our values and aspirations. There are many ways to define "community," but I prefer to think of it as a group of individuals united by shared values, goals, or experiences - people who genuinely understand and celebrate each other's journeys.

This adult need for community differs from the child's validation-seeking in important ways. Where a child seeks approval from authority figures, adults seek connection with peers. Where a child's validation is often about being "good enough," adult community engagement is about being part of something larger than ourselves. It's about finding our tribe, our “people” - who celebrate our wins and understand the struggle behind them.

For me, my Strava "community" is intentionally small: a tight group of friends and family members who share a similar excitement. When I post a ride, I'm not broadcasting to hundreds of followers. I'm sharing with people who understand what that particular workout meant to me, who know my goals, and who are on their own parallel journeys. For me, fitness is intimate, and I prefer to keep that community small, with a more expansive approach on other platforms.

We similarly seek workout partners for both the accountability and for the shared experience of pushing through difficulty together. Many of my patients prefer fitness classes to individual workouts for the same reasons. This is where healthy data sharing and community intersect beautifully. When we share our metrics with people who care about and understand our progress, data becomes a language of connection rather than numbers on a screen. Another dear friend, Dr. Michelle Nguyen, and I have wondered what a group primary care practice might look like - a place for community and shared accountability on health goals where patients are connected rather than siloed. A tricky concept, for another post.

Taking a step outside the world of fitness, the human desire to share our victories and struggles plays out everywhere. We can mention group therapy, book clubs, sports teams, but this is maybe most clearly demonstrated by the defining mode of connection in 2025 known as the “group chat.” Life is very hard, and it’s often easier to do hard things together.

The Individual Equation

These three forces aren't prescriptive categories of right and wrong, but they are the human realities that shape how we pursue health and self-improvement. My goal is to understand these needs, to recognize them when they serve our growth, and to recognize when they might be holding us back.

As a physician, I use my understanding of these three forces to assess where people are in this moment of their lives, and thus determine how I can be the most effective partner in their health journey. Every human has a unique relationship with their numbers, whether it's the anxiety that comes with waiting for lab results, the frustration of a fitness tracker that didn't record their morning run, or the guilt associated with logging what they ate yesterday.

Understanding this individual relationship is crucial because the same piece of data that motivates one person to make positive changes might send another into a spiral of self-criticism or avoidance. Some patients need more structure and data to build awareness; others need permission to step back from the numbers and trust their bodies. Some thrive on community accountability; others keep their journeys close to the chest. Acknowledging these forces openly creates space for more honest conversations, and understanding where each person sits across these dimensions allows me to meet them where they are rather than where I think they should be.

By developing this same self-awareness (understanding your own relationship with data, validation, and community), you can identify the structures and support systems that will serve your goals, and guide the people in your corner (whether a doctor, coach, friend, or romantic partner) on how to best help you succeed.

**

And now, instead of sharing my ride with my Strava community, I've shared this post with you, my Substack community.

I certainly hope you like it 🫠

Psyched to see the 2×2 table make its well-deserved debut!